South Korea’s memory makers have turned a feeding frenzy into headline-grabbing rewards. SK Hynix handed out an eye‑watering average year‑end bonus equivalent to roughly 136 million won per employee—about RMB 640,000—after a bumper year driven by demand for artificial‑intelligence infrastructure. The bonanza is not charity: it is the visible tip of a deep reallocation of capacity and capital toward the specialised memory needed by data centres.

The shift is simple in arithmetic and brutal in consequence. Hyperscalers and AI companies are buying High‑Bandwidth Memory (HBM) and large SSD capacity in volumes and prices that dwarf ordinary consumer demand. Producing HBM consumes far more wafer capacity than commodity NAND or DRAM; it is also far more profitable. Faced with predictable, high‑value contracts from Microsoft, Google and Amazon, Samsung and SK Hynix have moved significant capacity away from consumer flash memory to serve AI customers.

That reallocation is already reshaping markets. The two South Korean giants control roughly 60 percent of high‑end memory supply, and both have trimmed NAND output plans in favour of HBM lines. The immediate effect has been a dramatic rise in memory prices—component costs for consumer devices have jumped 40–60 percent in recent months—and, more worrying, a structural squeeze on capacity for phones and PCs.

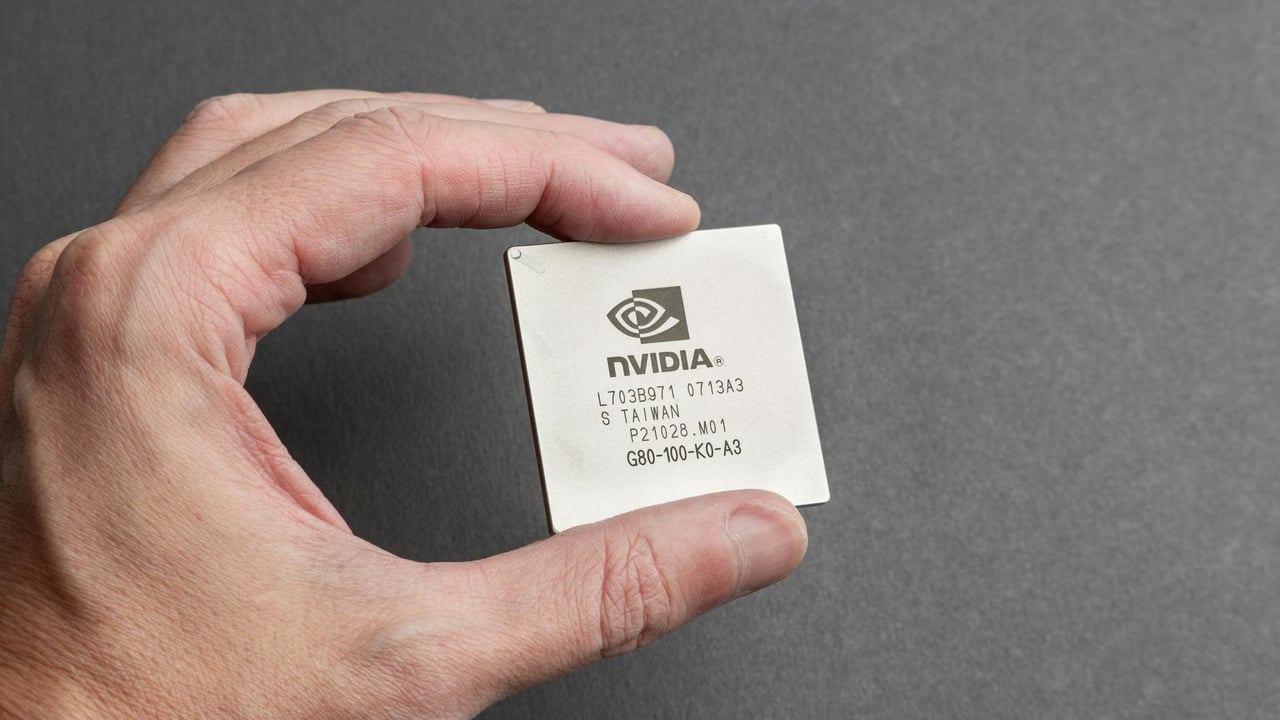

The demand side looks almost inexorable. New AI accelerators are paired with gargantuan storage requirements: Nvidia’s next‑generation designs, for example, require on the order of 1,152 terabytes of SSD per unit—ten times prior generations—and Citigroup estimates this could absorb more than 115 million terabytes of storage capacity by 2027. When deep‑pocketed hyperscalers and slim‑margin consumer electronics manufacturers compete for the same chips, the outcome is predictable: hyperscalers win.

Downstream consequences are bifurcated but clear. In the budget smartphone segment, manufacturers typically choose to preserve low shelf prices by quietly downgrading components—camera modules, screen materials, metal frames—so devices look the same on the surface while delivering less. At the top end, original equipment manufacturers exercise stronger pricing power: larger‑capacity models and premium phones are being marked up to capture rising memory costs, while marketing emphasizes AI features as justification.

The PC market is being pulled along. ‘AI PCs’ with 16GB or more of memory become the new baseline, and vendors including Lenovo, Dell and HP have warned of overall price increases of 15–20 percent. That combination—higher entry prices for capable machines and a weaker value proposition for incremental upgrades—risks lengthening refresh cycles and creating a negative feedback loop of slower sales and higher per‑unit costs.

The lavish bonuses and the factory‑building that funds future HBM supply are two sides of the same strategic bet. Semiconductor groups are using cash to retain scarce engineering talent and to buy capacity with large capital expenditures. SK Hynix has committed a substantial share of its profits to employee bonuses over coming years and has dramatically scaled up investment plans for new fabs and clusters. For those firms, paying out windfalls today is a defensive move to stay competitive in a market where time to market and process leadership matter enormously.

The broader implication is that consumers are beginning to underwrite the cost of an AI infrastructure build‑out. For two decades electronics benefited from steady cost declines driven by Moore’s Law and abundant commodity memory. That deflationary trend is losing force as compute and high‑bandwidth memory become scarce, expensive inputs. ‘Compute inflation’—where the price of end‑user devices is increasingly set by the price of high‑end memory and storage—may be the defining economic consequence of AI’s rapid hardware expansion.

There are geopolitical and policy angles to watch. Memory production remains concentrated in a few firms and locations, leaving global supply vulnerable to shocks and strategic rivalry. Governments may feel pressure to subsidise capacity, tighten export controls or support domestic alternatives, all of which would complicate an already strained market. Meanwhile, downstream manufacturers must weigh whether to pass costs to consumers, redesign products, or pursue longer‑term hedges and vertical integrations.

For ordinary buyers the choice is uncomfortable and immediate: pay more for nominally better devices, accept quietly downgraded hardware at the same price, or postpone purchases. What looks like a corporate payday in Seoul is, in effect, a price signal that the era of ever‑cheaper consumer electronics is over, replaced by an economy where building global AI scale imposes a tangible cost on the public.